0. Overview

- Over time, things change in a database:

- The query throughput increases, so you want to add more CPUs to handle the load

- The dataset size increases, so you want to add more disks and RAM to store it

- A machine fails, and other machines need to take over the failed machine’s responsibilities

- All of these changes call for data and requests to be moved from one node to another. The process of moving load from one node in the cluster to another is called rebalancing. No matter which partitioning scheme is used, rebalancing is usually expected to meet some minimum requirements:

- After rebalancing, the load (data storage, read and write requests) should be shared fairly between the nodes in the cluster

- While rebalancing is happening, the database should continue accepting reads and writes

- No more data than necessary should be moved between nodes, to make rebalancing fast and to minimize the network and disk I/O load

1. Strategies for Rebalancing

- There are a few different ways of assigning partitions to nodes

1.1. How not to do it: hash mod N

- When partitioning by the hash of a key, it’s best to divide the possible hashes into ranges and assign each range to a partition (e.g., assign key to partition 0 if 0 ≤ hash(key) < b0, to partition 1 if b0 ≤ hash(key) < b1, …)

- The problem with the “hash(key) mod N” approach is that if the number of nodes N changes, most of the keys will need to be moved from one node to another. Such frequent moves make rebalancing excessively expensive

1.2. Fixed number of partitions

- There is a fairly simple solution: create many more partitions than there are nodes, and assign several partitions to each node. Now, if a node is added to the cluster, the new node can steal a few partitions from every existing node until partitions are fairly distributed once again. If a node is removed from the cluster, the same happens in reverse

- Only entire partitions are moved between nodes. The number of partitions does not change, nor does the assignment of keys to partitions. The only thing that changes is the assignment of partitions to nodes

- This change of assignment is not immediate—it takes some time to transfer a large amount of data over the network—so the old assignment of partitions is used for any reads and writes that happen while the transfer is in progress

- In principle, you can even account for mismatched hardware in your cluster: by assigning more partitions to nodes that are more powerful, you can force those nodes to take a greater share of the load

- The number of partitions is usually fixed when the database is first set up and not changed afterward. Although in principle it’s possible to split and merge partitions, a fixed number of partitions is operationally simpler, and so many fixed-partition databases choose not to implement partition splitting

- Thus, the number of partitions configured at the outset is the maximum number of nodes you can have, so you need to choose it high enough to accommodate future growth. However, each partition also has management overhead, so it’s counterproductive to choose too high a number

- Choosing the right number of partitions is difficult if the total size of the dataset is highly variable (for example, if it starts small but may grow much larger over time). Since each partition contains a fixed fraction of the total data, the size of each partition grows proportionally to the total amount of data in the cluster. If partitions are very large, rebalancing and recovery from node failures become expensive. But if partitions are too small, they incur too much overhead. The best performance is achieved when the size of partitions is “just right”, neither too big nor too small, which can be hard to achieve if the number of partitions is fixed but the dataset size varies

1.3. Dynamic partitioning

For databases that use key range partitioning, a fixed number of partitions with fixed boundaries would be very inconvenient: if you got the boundaries wrong, you could end up with all of the data in one partition and all of the other partitions empty. Reconfiguring the partition boundaries manually would be very tedious

For that reason, key range–partitioned databases such as HBase and RethinkDB create partitions dynamically. When a partition grows to exceed a configured size (on HBase, the default is 10 GB), it is split into two partitions so that approximately half of the data ends up on each side of the split. Conversely, if lots of data is deleted and a partition shrinks below some threshold, it can be merged with an adjacent partition. After a large partition has been split, one of its two halves can be transferred to another node in order to balance the load. In the case of HBase, the transfer of partition files happens through HDFS. Also, HBase and MongoDB allow an initial set of partitions to be configured on an empty database, this is called pre-splitting

Dynamic partitioning is not only suitable for key range–partitioned data, but can equally well be used with hash-partitioned data. An advantage of dynamic partitioning is that the number of partitions adapts to the total data volume. If there is only a small amount of data, a small number of partitions is sufficient, so overheads are small; if there is a huge amount of data, the size of each individual partition is limited to a configurable maximum

1.4. Partitioning proportionally to nodes

- With dynamic partitioning, the number of partitions is proportional to the size of the dataset. On the other hand, with a fixed number of partitions, the size of each partition is proportional to the size of the dataset. In both of these cases, the number of partitions is independent of the number of nodes

- A third option, used by Cassandra and Ketama, is to make the number of partitions proportional to the number of nodes—in other words, to have a fixed number of partitions per node. Since a larger data volume generally requires a larger number of nodes to store, this approach also keeps the size of each partition fairly stable

- When a new node joins the cluster, it randomly chooses a fixed number of existing partitions to split, and then takes ownership of one half of each of those split partitions while leaving the other half of each partition in place. The randomization can produce unfair splits, but when averaged over a larger number of partitions (in Cassandra, 256 partitions per node by default), the new node ends up taking a fair share of the load from the existing nodes. Cassandra 3.0 introduced an alternative rebalancing algorithm that avoids unfair splits

- Picking partition boundaries randomly requires that hash-based partitioning is used (so the boundaries can be picked from the range of numbers produced by the hash function). Indeed, this approach corresponds most closely to the original definition of consistent hashing. Newer hash functions can achieve a similar effect with lower metadata overhead

1.5. Automatic or Manual Rebalancing

- There is a gradient between fully automatic rebalancing (the system decides automatically when to move partitions from one node to another, without any administrator interaction) and fully manual (the assignment of partitions to nodes is explicitly configured by an administrator, and only changes when the administrator explicitly reconfigures it). For example, Couchbase, Riak, and Voldemort generate a suggested partition assignment automatically, but require an administrator to commit it before it takes effect

- Fully automated rebalancing can be convenient, because there is less operational work to do for normal maintenance. However, it can be unpredictable. Rebalancing is an expensive operation, because it requires rerouting requests and moving a large amount of data from one node to another. If it is not done carefully, this process can overload the network or the nodes and harm the performance of other requests while the rebalancing is in progress

- Such automation can be dangerous in combination with automatic failure detection. For example, say one node is overloaded and is temporarily slow to respond to requests. The other nodes conclude that the overloaded node is dead, and automatically rebalance the cluster to move load away from it. This puts additional load on the overloaded node, other nodes, and the network—making the situation worse and potentially causing a cascading failure

2. Request Routing

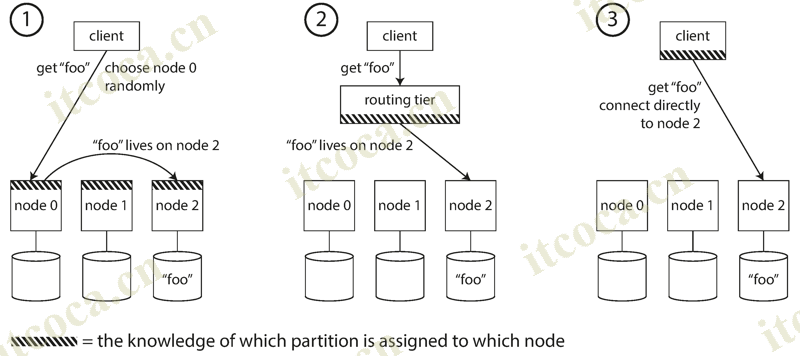

- As partitions are rebalanced, the assignment of partitions to nodes changes. Somebody needs to stay on top of those changes in order to know which node to connect to. This is an instance of a more general problem called service discovery, which isn’t limited to just databases. Any piece of software that is accessible over a network has this problem, especially if it is aiming for high availability. There are a few different approaches:

- Allow clients to contact any node (e.g., via a round-robin load balancer). If that node coincidentally owns the partition to which the request applies, it can handle the request directly; otherwise, it forwards the request to the appropriate node, receives the reply, and passes the reply along to the client

- Send all requests from clients to a routing tier first, which determines the node that should handle each request and forwards it accordingly. This routing tier does not itself handle any requests; it only acts as a partition-aware load balancer

- Require that clients be aware of the partitioning and the assignment of partitions to nodes. In this case, a client can connect directly to the appropriate node, without any intermediary

- Components that make routing decisions should be aware of the changes in node partition assignments. This is a challenging problem, because it is important that all participants agree—otherwise requests would be sent to the wrong nodes and not handled correctly. There are protocols for achieving consensus in a distributed system

- Many distributed data systems rely on a separate coordination service such as ZooKeeper to keep track of this cluster metadata. Each node registers itself in ZooKeeper, and ZooKeeper maintains the authoritative mapping of partitions to nodes. Other actors, such as the routing tier or the partitioning-aware client, can subscribe to this information in ZooKeeper. Whenever a partition changes ownership, or a node is added or removed, ZooKeeper notifies the routing tier so that it can keep its routing information up to date

- Cassandra and Riak take a different approach: they use a gossip protocol among the nodes to disseminate any changes in cluster state. Requests can be sent to any node, and that node forwards them to the appropriate node for the requested partition. This model puts more complexity in the database nodes but avoids the dependency on an external coordination service such as ZooKeeper

- Couchbase does not rebalance automatically, which simplifies the design. Normally it is configured with a routing tier called moxi, which learns about routing changes from the cluster nodes

- When using a routing tier or when sending requests to a random node, clients still need to find the IP addresses to connect to. These are not as fast-changing as the assignment of partitions to nodes, so it is often sufficient to use DNS for this purpose

2.1. Parallel Query Execution

- So far we have focused on very simple queries that read or write a single key (plus scatter/gather queries in the case of document-partitioned secondary indexes). This is about the level of access supported by most NoSQL distributed datastores

- However, massively parallel processing (MPP) relational database products, often used for analytics, are much more sophisticated in the types of queries they support. A typical data warehouse query contains several join, filtering, grouping, and aggregation operations. The MPP query optimizer breaks this complex query into a number of execution stages and partitions, many of which can be executed in parallel on different nodes of the database cluster. Queries that involve scanning over large parts of the dataset particularly benefit from such parallel execution

References

- Designing Data-Intensive Application